Plutonium: Difference between revisions

m →In popular culture: ch hyphen to en dash |

Citation bot (talk | contribs) Added bibcode. | Use this bot. Report bugs. | Suggested by Whoop whoop pull up | #UCB_webform 2269/3364 |

||

| (34 intermediate revisions by 26 users not shown) | |||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

{{distinguish|Polonium}} |

{{distinguish|Polonium}} |

||

{{pp-semi-indef}} |

{{pp-semi-indef}} |

||

{{pp-move |

{{pp-move}} |

||

{{infobox plutonium}} |

{{infobox plutonium}} |

||

'''Plutonium''' is a |

'''Plutonium''' is a [[chemical element]]; it has [[Chemical symbol|symbol]] '''Pu''' and [[atomic number]] 94. It is an [[actinide]] [[metal]] of silvery-gray appearance that [[tarnish]]es when exposed to air, and forms a dull coating [[plutonium(IV) oxide|when oxidized]]. The element normally exhibits six [[allotrope]]s and four [[oxidation state]]s. It reacts with [[carbon]], [[halogen]]s, [[nitrogen]], [[silicon]], and [[hydrogen]]. When exposed to moist air, it forms [[oxide]]s and [[hydride]]s that can expand the sample up to 70% in volume, which in turn flake off as a powder that is [[pyrophoricity|pyrophoric]]. It is [[radioactive]] and can accumulate in [[bone]]s, which makes the handling of plutonium dangerous. |

||

Plutonium was first synthetically produced and isolated in late 1940 and early 1941, by a [[Deuterium|deuteron]] bombardment of [[uranium-238]] in the {{convert|1.5|m|in|-1|adj=on}} [[cyclotron]] at the [[University of California, Berkeley]]. First, [[neptunium-238]] ([[half-life]] 2.1 days) was synthesized, which subsequently [[Beta decay|beta-decayed]] to form the new element with atomic number 94 and atomic weight 238 (half-life 88 years). Since [[uranium]] had been named after the planet [[Uranus]] and [[neptunium]] after the planet [[Neptune]], element 94 was named after [[Pluto]], which at the time was considered to be a planet as well. Wartime secrecy prevented the University of California team from publishing its discovery until 1948. |

Plutonium was first synthetically produced and isolated in late 1940 and early 1941, by a [[Deuterium|deuteron]] bombardment of [[uranium-238]] in the {{convert|1.5|m|in|-1|adj=on}} [[cyclotron]] at the [[University of California, Berkeley]]. First, [[neptunium-238]] ([[half-life]] 2.1 days) was synthesized, which subsequently [[Beta decay|beta-decayed]] to form the new element with atomic number 94 and atomic weight 238 (half-life 88 years). Since [[uranium]] had been named after the planet [[Uranus]] and [[neptunium]] after the planet [[Neptune]], element 94 was named after [[Pluto]], which at the time was considered to be a planet as well. Wartime secrecy prevented the University of California team from publishing its discovery until 1948. |

||

Plutonium is the element with the highest atomic number to occur in nature. Trace quantities arise in natural uranium-238 deposits when uranium-238 captures neutrons emitted by decay of other uranium-238 atoms. |

Plutonium is the element with the highest atomic number known to occur in nature. Trace quantities arise in natural uranium-238 deposits when uranium-238 captures neutrons emitted by decay of other uranium-238 atoms. The heavy isotope [[plutonium-244]] has a half-life long enough that extreme [[trace element|trace quantities]] should have survived [[primordial nuclide|primordially]] (from the Earth's formation) to the present, but so far experiments have not yet been sensitive enough to detect it. |

||

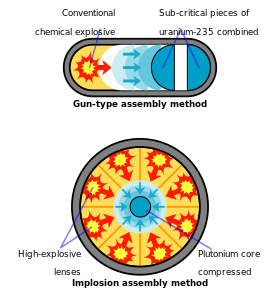

Both [[plutonium-239]] and [[plutonium-241]] are [[fissile]], meaning that they can sustain a [[nuclear chain reaction]], leading to applications in [[nuclear weapon]]s and [[nuclear reactor]]s. [[Plutonium-240]] exhibits a high rate of [[spontaneous fission]], raising the [[neutron flux]] of any sample containing it. The presence of plutonium-240 limits a plutonium sample's usability for weapons or its quality as reactor fuel, and the percentage of plutonium-240 determines its [[reactor-grade plutonium|grade]] ([[weapons-grade]], fuel-grade, or reactor-grade). [[Plutonium-238]] has a half-life of 87.7 years and emits [[alpha particle]]s. It is a heat source in [[radioisotope thermoelectric generator]]s, which are used to power some [[spacecraft]]. Plutonium isotopes are expensive and inconvenient to separate, so particular isotopes are usually manufactured in specialized reactors. |

Both [[plutonium-239]] and [[plutonium-241]] are [[fissile]], meaning that they can sustain a [[nuclear chain reaction]], leading to applications in [[nuclear weapon]]s and [[nuclear reactor]]s. [[Plutonium-240]] exhibits a high rate of [[spontaneous fission]], raising the [[neutron flux]] of any sample containing it. The presence of plutonium-240 limits a plutonium sample's usability for weapons or its quality as reactor fuel, and the percentage of plutonium-240 determines its [[reactor-grade plutonium|grade]] ([[weapons-grade]], fuel-grade, or reactor-grade). [[Plutonium-238]] has a half-life of 87.7 years and emits [[alpha particle]]s. It is a heat source in [[radioisotope thermoelectric generator]]s, which are used to power some [[spacecraft]]. Plutonium isotopes are expensive and inconvenient to separate, so particular isotopes are usually manufactured in specialized reactors. |

||

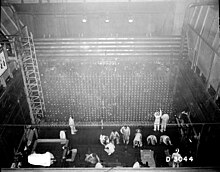

Producing plutonium in useful quantities for the first time was a major part of the [[Manhattan Project]] during [[World War II]] that developed the first atomic bombs. The [[Fat Man]] bombs used in the [[Trinity (nuclear test)|Trinity]] [[nuclear test]] in July 1945, and in the [[bombing of Nagasaki]] in August 1945, had plutonium [[pit (nuclear weapon)|cores]]. [[Human radiation experiments]] studying plutonium were conducted without [[informed consent]], and several [[criticality accident]]s, some lethal, occurred after the war. Disposal of [[nuclear waste|plutonium waste]] from [[nuclear power plant]]s and [[nuclear disarmament|dismantled nuclear weapons]] built during the [[Cold War]] is a [[nuclear proliferation|nuclear-proliferation]] and environmental concern. Other sources of [[plutonium in the environment]] are [[nuclear fallout|fallout]] from numerous above-ground nuclear tests, now [[Partial Test Ban Treaty|banned]]. |

Producing plutonium in useful quantities for the first time was a major part of the [[Manhattan Project]] during [[World War II]] that developed the first atomic bombs. The [[Fat Man]] bombs used in the [[Trinity (nuclear test)|Trinity]] [[nuclear test]] in July 1945, and in the [[bombing of Nagasaki]] in August 1945, had plutonium [[pit (nuclear weapon)|cores]]. [[Human radiation experiments]] studying plutonium were conducted without [[informed consent]], and several [[criticality accident]]s, some lethal, occurred after the war. Disposal of [[nuclear waste|plutonium waste]] from [[nuclear power plant]]s and [[nuclear disarmament|dismantled nuclear weapons]] built during the [[Cold War]] is a [[nuclear proliferation|nuclear-proliferation]] and environmental concern. Other sources of [[plutonium in the environment]] are [[nuclear fallout|fallout]] from numerous above-ground nuclear tests, which are now [[Partial Test Ban Treaty|banned]]. |

||

==Characteristics== |

==Characteristics== |

||

===Physical properties=== |

===Physical properties=== |

||

Plutonium, like most metals, has a bright silvery appearance at first, much like [[nickel]], but it [[plutonium(IV) oxide|oxidizes]] very quickly to a dull gray, although yellow and olive green are also reported.<ref name="WISER">{{Cite web |title=Plutonium, Radioactive |url=http://webwiser.nlm.nih.gov/getSubstanceData.do;jsessionid=89B673C34252C77B4C276F2B2D0E4260?substanceID=419&displaySubstanceName=Plutonium,%20Radioactive&UNNAID=&STCCID=&selectedDataMenuItemID=44 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://www.webcitation.org/618bQEh1E?url=http://webwiser.nlm.nih.gov/getSubstanceData.do;jsessionid=89B673C34252C77B4C276F2B2D0E4260?substanceID=419&displaySubstanceName=Plutonium%2C%20Radioactive&UNNAID=&STCCID=&selectedDataMenuItemID=44 |archive-date=August 22, 2011 |access-date=November 23, 2008 |website=Wireless Information System for Emergency Responders (WISER) |publisher=U.S. National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health |location=Bethesda (MD)}} (public domain text)</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |date=2008 |title=Nitric acid processing |url=http://www.lanl.gov/discover/publications/actinide-research-quarterly/ |url-status=live |journal=Actinide Research Quarterly |location=Los Alamos (NM) |publisher=Los Alamos National Laboratory |issue=3rd quarter |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160918212329/http://www.lanl.gov/discover/publications/actinide-research-quarterly/ |archive-date=September 18, 2016 |access-date=February 9, 2010 |quote=While plutonium dioxide is normally olive green, samples can be various colors. It is generally believed that the color is a function of chemical purity, stoichiometry, particle size, and method of preparation, although the color resulting from a given preparation method is not always reproducible.}}</ref> At [[room temperature]] plutonium is in its [[allotropes of plutonium|α (''alpha'') form]]. This, the most common structural form of the element ([[allotrope]]), is about as hard and brittle as [[cast iron#Grey cast iron|gray cast iron]] unless it is [[alloy]]ed with other metals to make it soft and ductile. Unlike most metals, it is not a good conductor of [[thermal conductivity|heat]] or [[electrical conductivity|electricity]]. It has a low [[melting point]] ({{convert|640|°C|disp=comma}}) and an unusually high [[boiling point]] ({{convert|3228|°C|disp=comma}}).<ref name="WISER" /> This gives a large range of temperatures (over 2,500 kelvin wide) at which plutonium is liquid, but this range is neither the greatest among all actinides nor among all metals.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Liquid Range |url=https://www.webelements.com/periodicity/liquid_range/ |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220227135806/https://www.webelements.com/periodicity/liquid_range/ |archive-date=February 27, 2022 |access-date=28 February 2022 |website=webelements.com}}</ref> The low melting point as well as the reactivity of the native metal compared to the oxide leads to plutonium oxides being a preferred form for applications such as nuclear fission reactor fuel ([[MOX-fuel]]). |

|||

Plutonium, like most metals, has a bright silvery appearance at first, much like [[nickel]], but it [[plutonium(IV) oxide|oxidizes]] very quickly to a dull gray, although yellow and olive green are also reported.<ref name = "WISER">{{cite web |

|||

|url = http://webwiser.nlm.nih.gov/getSubstanceData.do;jsessionid=89B673C34252C77B4C276F2B2D0E4260?substanceID=419&displaySubstanceName=Plutonium,%20Radioactive&UNNAID=&STCCID=&selectedDataMenuItemID=44 |

|||

|publisher = U.S. National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health |

|||

|location = Bethesda (MD) |

|||

|title = Plutonium, Radioactive |

|||

|work = Wireless Information System for Emergency Responders (WISER) |

|||

|access-date = November 23, 2008 |

|||

|archive-url = https://www.webcitation.org/618bQEh1E?url=http://webwiser.nlm.nih.gov/getSubstanceData.do;jsessionid=89B673C34252C77B4C276F2B2D0E4260?substanceID=419&displaySubstanceName=Plutonium%2C%20Radioactive&UNNAID=&STCCID=&selectedDataMenuItemID=44 |

|||

|archive-date = August 22, 2011 |

|||

|url-status = dead |

|||

}} (public domain text)</ref><ref>{{cite journal |

|||

|title = Nitric acid processing |

|||

|url = http://www.lanl.gov/discover/publications/actinide-research-quarterly/ |

|||

|journal = Actinide Research Quarterly |

|||

|date = 2008 |

|||

|issue = 3rd quarter |

|||

|publisher = Los Alamos National Laboratory |

|||

|location = Los Alamos (NM) |

|||

|quote = While plutonium dioxide is normally olive green, samples can be various colors. It is generally believed that the color is a function of chemical purity, stoichiometry, particle size, and method of preparation, although the color resulting from a given preparation method is not always reproducible. |

|||

|access-date = February 9, 2010 |

|||

|archive-date = September 18, 2016 |

|||

|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20160918212329/http://www.lanl.gov/discover/publications/actinide-research-quarterly/ |

|||

|url-status = live |

|||

}}</ref> At room temperature plutonium is in its [[allotropes of plutonium|α (''alpha'') form]]. This, the most common structural form of the element ([[allotrope]]), is about as hard and brittle as [[cast iron#Grey cast iron|gray cast iron]] unless it is [[alloy]]ed with other metals to make it soft and ductile. Unlike most metals, it is not a good conductor of [[thermal conductivity|heat]] or [[electrical conductivity|electricity]]. It has a low [[melting point]] ({{convert|640|°C|disp=comma}}) and an unusually high [[boiling point]] ({{convert|3228|°C|disp=comma}}).<ref name = "WISER" /> This gives a large range of temperatures (over 2,500 kelvin wide) at which plutonium is liquid, but this range is neither the greatest among all actinides nor among all metals.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.webelements.com/periodicity/liquid_range/ |title=Liquid Range |website=webelements.com |access-date=28 February 2022 |archive-date=February 27, 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220227135806/https://www.webelements.com/periodicity/liquid_range/ |url-status=live }}</ref> The low melting point as well as the reactivity of the native metal compared to the oxide leads to plutonium oxides being a preferred form for applications such as nuclear fission reactor fuel ([[MOX-fuel]]). |

|||

[[Alpha decay]], the release of a high-energy [[helium]] nucleus, is the most common form of [[radioactive decay]] for plutonium.<ref name |

[[Alpha decay]], the release of a high-energy [[helium]] nucleus, is the most common form of [[radioactive decay]] for plutonium.<ref name="NNDC" /> A 5 kg mass of <sup>239</sup>Pu contains about {{val|12.5|e=24}} atoms. With a half-life of 24,100 years, about {{val|11.5|e=12}} of its atoms decay each second by emitting a 5.157 [[MeV]] alpha particle. This amounts to 9.68 watts of power. Heat produced by the deceleration of these alpha particles makes it warm to the touch.<ref name="Heiserman1992">{{harvnb|Heiserman|1992|p=338}}</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Rhodes|1986|pp=659–660}} [[Leona Marshall]]: "When you hold a lump of it in your hand, it feels warm, like a live rabbit"</ref> {{chem|238|Pu}} due to its much shorter [[half life]] heats up to much higher temperatures and glows red hot with [[blackbody radiation]] if left without external heating or cooling. This heat has been used in [[Radioisotope thermoelectric generator]]s (see below). |

||

{{harvnb|Rhodes|1986|pp=659–660}} [[Leona Marshall]]: "When you hold a lump of it in your hand, it feels warm, like a live rabbit"</ref> {{chem|238|Pu}} due to its much shorter [[half life]] heats up to much higher temperatures and glows red hot with [[blackbody radiation]] if left without external heating or cooling. This heat has been used in [[Radioisotope thermoelectric generator]]s (see below). |

|||

[[Resistivity]] is a measure of how strongly a material opposes the flow of [[electric current]]. The resistivity of plutonium at room temperature is very high for a metal, and it gets even higher with lower temperatures, which is unusual for metals.<ref name |

[[Resistivity]] is a measure of how strongly a material opposes the flow of [[electric current]]. The resistivity of plutonium at room temperature is very high for a metal, and it gets even higher with lower temperatures, which is unusual for metals.<ref name="Miner1968p544" /> This trend continues down to 100 [[Kelvin|K]], below which resistivity rapidly decreases for fresh samples.<ref name="Miner1968p544" /> Resistivity then begins to increase with time at around 20 K due to radiation damage, with the rate dictated by the isotopic composition of the sample.<ref name="Miner1968p544" /> |

||

Because of self-irradiation, a sample of plutonium |

Because of self-irradiation, a sample of plutonium [[Fatigue (material)|fatigue]]s throughout its crystal structure, meaning the ordered arrangement of its atoms becomes disrupted by radiation with time.<ref name="HeckerPlutonium" /> Self-irradiation can also lead to [[annealing (metallurgy)|annealing]] which counteracts some of the fatigue effects as temperature increases above 100 K.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Hecker |first1=Siegfried S. |last2=Martz, Joseph C. |date=2000 |title=Aging of Plutonium and Its Alloys |url=http://library.lanl.gov/cgi-bin/getfile?00818029.pdf |url-status=live |journal=[[Los Alamos Science]] |location=Los Alamos, New Mexico |publisher=Los Alamos National Laboratory |issue=26 |page=242 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210428114802/https://library.lanl.gov/cgi-bin/getfile?00818029.pdf |archive-date=April 28, 2021 |access-date=February 15, 2009}}</ref> |

||

|title = Aging of Plutonium and Its Alloys |

|||

|page = 242 |

|||

|journal = [[Los Alamos Science]] |

|||

|date = 2000 |

|||

|issue = 26 |

|||

|url = http://library.lanl.gov/cgi-bin/getfile?00818029.pdf |

|||

|last = Hecker |

|||

|first = Siegfried S. |

|||

|author2 = Martz, Joseph C. |

|||

|location = Los Alamos, New Mexico |

|||

|publisher = Los Alamos National Laboratory |

|||

|access-date = February 15, 2009 |

|||

|archive-date = April 28, 2021 |

|||

|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20210428114802/https://library.lanl.gov/cgi-bin/getfile?00818029.pdf |

|||

|url-status = live |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

Unlike most materials, plutonium increases in density when it melts, by 2.5%, but the liquid metal exhibits a linear decrease in density with temperature.<ref name="Miner1968p544">{{harvnb|Miner|1968|p = 544}}</ref> Near the melting point, the liquid plutonium has very high [[viscosity]] and [[surface tension]] compared to other metals.<ref name |

Unlike most materials, plutonium increases in density when it melts, by 2.5%, but the liquid metal exhibits a linear decrease in density with temperature.<ref name="Miner1968p544">{{harvnb|Miner|1968|p = 544}}</ref> Near the melting point, the liquid plutonium has very high [[viscosity]] and [[surface tension]] compared to other metals.<ref name="HeckerPlutonium" /> |

||

===Allotropes=== |

===Allotropes=== |

||

{{Main|Allotropes of plutonium}} |

{{Main|Allotropes of plutonium}} |

||

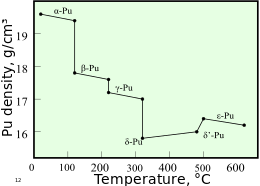

[[File:Plutonium density-eng.svg|thumb|upright=1.2|Plutonium has six allotropes at ambient pressure: '''alpha''' (α), '''beta''' (β), '''gamma''' (γ), '''delta''' (δ), '''delta prime''' (δ'), and '''epsilon''' (ε)<ref name |

[[File:Plutonium density-eng.svg|thumb|upright=1.2|Plutonium has six allotropes at ambient pressure: '''alpha''' (α), '''beta''' (β), '''gamma''' (γ), '''delta''' (δ), '''delta prime''' (δ'), and '''epsilon''' (ε).<ref name="Baker1983" />|alt=A graph showing change in density with increasing temperature upon sequential phase transitions between alpha, beta, gamma, delta, delta' and epsilon phases]] |

||

Plutonium normally has six [[allotrope]]s and forms a seventh (zeta, ζ) at high temperature within a limited pressure range.<ref name="Baker1983">{{Cite journal |last1=Baker |first1=Richard D. |last2=Hecker |first2=Siegfried S. |last3=Harbur |first3=Delbert R. |date=1983 |title=Plutonium: A Wartime Nightmare but a Metallurgist's Dream |url=http://library.lanl.gov/cgi-bin/getfile?07-16.pdf |url-status=live |journal=Los Alamos Science |publisher=Los Alamos National Laboratory |pages=148, 150–151 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111017034523/http://library.lanl.gov/cgi-bin/getfile?07-16.pdf |archive-date=October 17, 2011 |access-date=February 15, 2009}}</ref><!-- Note: page 148 --> These allotropes, which are different structural modifications or forms of an element, have very similar [[internal energy|internal energies]] but significantly varying [[density|densities]] and [[crystal structure]]s. This makes plutonium very sensitive to changes in temperature, pressure, or chemistry, and allows for dramatic volume changes following [[phase transition]]s from one allotropic form to another.<ref name="HeckerPlutonium">{{Cite journal |last=Hecker |first=Siegfried S. |date=2000 |title=Plutonium and its alloys: from atoms to microstructure |url=https://fas.org/sgp/othergov/doe/lanl/pubs/00818035.pdf |url-status=live |journal=Los Alamos Science |volume=26 |pages=290–335 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090224204042/http://www.fas.org/sgp/othergov/doe/lanl/pubs/00818035.pdf |archive-date=February 24, 2009 |access-date=February 15, 2009}}</ref> The densities of the different allotropes vary from 16.00 g/cm<sup>3</sup> to 19.86 g/cm<sup>3</sup>.<ref name="CRC2006p4-27" /> |

|||

Plutonium normally has six [[allotrope]]s and forms a seventh (zeta, ζ) at high temperature within a limited pressure range.<ref name = "Baker1983">{{cite journal |

|||

|url = http://library.lanl.gov/cgi-bin/getfile?07-16.pdf |

|||

|title = Plutonium: A Wartime Nightmare but a Metallurgist's Dream |

|||

|last1 = Baker |

|||

|first1 = Richard D. |

|||

|last2 = Hecker |

|||

|first2 = Siegfried S. |

|||

|last3 = Harbur |

|||

|first3 = Delbert R. |

|||

|journal = Los Alamos Science |

|||

|date = 1983 |

|||

|publisher = Los Alamos National Laboratory |

|||

|pages = 148, 150–151 |

|||

|access-date = February 15, 2009 |

|||

|archive-date = October 17, 2011 |

|||

|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20111017034523/http://library.lanl.gov/cgi-bin/getfile?07-16.pdf |

|||

|url-status = live |

|||

}}</ref><!-- Note: page 148 --> These allotropes, which are different structural modifications or forms of an element, have very similar [[internal energy|internal energies]] but significantly varying [[density|densities]] and [[crystal structure]]s. This makes plutonium very sensitive to changes in temperature, pressure, or chemistry, and allows for dramatic volume changes following [[phase transition]]s from one allotropic form to another.<ref name = "HeckerPlutonium">{{cite journal |

|||

|first = Siegfried S. |

|||

|last = Hecker |

|||

|title = Plutonium and its alloys: from atoms to microstructure |

|||

|journal = Los Alamos Science |

|||

|volume = 26 |

|||

|date = 2000 |

|||

|pages = 290–335 |

|||

|url = https://fas.org/sgp/othergov/doe/lanl/pubs/00818035.pdf |

|||

|access-date = February 15, 2009 |

|||

|archive-date = February 24, 2009 |

|||

|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20090224204042/http://www.fas.org/sgp/othergov/doe/lanl/pubs/00818035.pdf |

|||

|url-status = live |

|||

}}</ref> The densities of the different allotropes vary from 16.00 g/cm<sup>3</sup> to 19.86 g/cm<sup>3</sup>.<ref name="CRC2006p4-27" /> |

|||

The presence of these many allotropes makes machining plutonium very difficult, as it changes state very readily. For example, the α form exists at room temperature in unalloyed plutonium. It has machining characteristics similar to [[cast iron]] but changes to the plastic and malleable β (''beta'') form at slightly higher temperatures.<ref name |

The presence of these many allotropes makes machining plutonium very difficult, as it changes state very readily. For example, the α form exists at room temperature in unalloyed plutonium. It has machining characteristics similar to [[cast iron]] but changes to the plastic and malleable β (''beta'') form at slightly higher temperatures.<ref name="Miner1968p542" /> The reasons for the complicated phase diagram are not entirely understood. The α form has a low-symmetry [[monoclinic crystal system|monoclinic]] structure, hence its brittleness, strength, compressibility, and poor thermal conductivity.<ref name="Baker1983" /> |

||

Plutonium in the δ (''delta'') form normally exists in the 310 °C to 452 °C range but is stable at room temperature when alloyed with a small percentage of [[gallium]], [[aluminium]], or [[cerium]], enhancing workability and allowing it to be [[welding|welded]].<ref name |

Plutonium in the δ (''delta'') form normally exists in the 310 °C to 452 °C range but is stable at room temperature when alloyed with a small percentage of [[gallium]], [[aluminium]], or [[cerium]], enhancing workability and allowing it to be [[welding|welded]].<ref name="Miner1968p542" /> The δ form has more typical metallic character, and is roughly as strong and malleable as aluminium.<ref name="Baker1983" /> In fission weapons, the explosive [[shock wave]]s used to compress a plutonium core will also cause a transition from the usual δ phase plutonium to the denser α form, significantly helping to achieve [[supercriticality]].{{citation needed|date=February 2023}} The ε phase, the highest temperature solid allotrope, exhibits anomalously high atomic [[self-diffusion]] compared to other elements.<ref name="HeckerPlutonium" /> |

||

===Nuclear fission=== |

===Nuclear fission=== |

||

[[File:Plutonium ring.jpg|right|upright=0.7|thumb|A ring of [[weapons-grade]] 99.96% pure electrorefined plutonium, enough for one [[nuclear weapon design#Plutonium pit|bomb core]]. The ring weighs 5.3 kg, is ca. 11 cm in diameter and its shape helps with [[nuclear criticality safety|criticality safety]].|alt=cylinder of Pu metal]] |

[[File:Plutonium ring.jpg|right|upright=0.7|thumb|A ring of [[weapons-grade]] 99.96% pure electrorefined plutonium, enough for one [[nuclear weapon design#Plutonium pit|bomb core]]. The ring weighs 5.3 kg, is ca. 11 cm in diameter and its shape helps with [[nuclear criticality safety|criticality safety]].|alt=cylinder of Pu metal]] |

||

Plutonium is a radioactive [[actinide]] metal whose [[isotope]], [[plutonium-239]], is one of the three primary [[fissile]] isotopes ([[uranium-233]] and [[uranium-235]] are the other two); [[plutonium-241]] is also highly fissile. To be considered fissile, an isotope's [[atomic nucleus]] must be able to break apart or [[nuclear fission|fission]] when struck by a [[neutron temperature|slow moving neutron]] and to release enough additional neutrons to sustain the [[nuclear chain reaction]] by splitting further nuclei.<ref>{{ |

Plutonium is a radioactive [[actinide]] metal whose [[isotope]], [[plutonium-239]], is one of the three primary [[fissile]] isotopes ([[uranium-233]] and [[uranium-235]] are the other two); [[plutonium-241]] is also highly fissile. To be considered fissile, an isotope's [[atomic nucleus]] must be able to break apart or [[nuclear fission|fission]] when struck by a [[neutron temperature|slow moving neutron]] and to release enough additional neutrons to sustain the [[nuclear chain reaction]] by splitting further nuclei.<ref>{{Cite web |date=November 20, 2014 |title=Glossary – Fissile material |url=https://www.nrc.gov/reading-rm/basic-ref/glossary/fissile-material.html |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150204223452/http://www.nrc.gov/reading-rm/basic-ref/glossary/fissile-material.html |archive-date=February 4, 2015 |access-date=February 5, 2015 |publisher=[[United States Nuclear Regulatory Commission]]}}</ref> |

||

|url = https://www.nrc.gov/reading-rm/basic-ref/glossary/fissile-material.html |

|||

|title = Glossary – Fissile material |

|||

|publisher = [[United States Nuclear Regulatory Commission]] |

|||

|date = November 20, 2014 |

|||

|access-date = February 5, 2015 |

|||

|archive-date = February 4, 2015 |

|||

|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20150204223452/http://www.nrc.gov/reading-rm/basic-ref/glossary/fissile-material.html |

|||

|url-status = live |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

Pure plutonium-239 may have a [[four factor formula|multiplication factor]] (k<sub>eff</sub>) larger than one, which means that if the metal is present in sufficient quantity and with an appropriate geometry (e.g., a sphere of sufficient size), it can form a [[critical mass]].<ref> |

Pure plutonium-239 may have a [[four factor formula|multiplication factor]] (k<sub>eff</sub>) larger than one, which means that if the metal is present in sufficient quantity and with an appropriate geometry (e.g., a sphere of sufficient size), it can form a [[critical mass]].<ref>{{harvnb|Asimov|1988|p=905}}</ref> During fission, a fraction of the [[nuclear binding energy]], which holds a nucleus together, is released as a large amount of [[Electromagnetism|electromagnetic]] and [[kinetic energy]] (much of the latter being quickly converted to thermal energy). Fission of a kilogram of plutonium-239 can produce an explosion equivalent to {{convert|21,000|tonTNT|lk=on}}. It is this energy that makes plutonium-239 useful in [[nuclear weapon]]s and [[nuclear reactor|reactors]].<ref name="Heiserman1992" /> |

||

{{harvnb|Asimov|1988|p=905}}</ref> During fission, a fraction of the [[nuclear binding energy]], which holds a nucleus together, is released as a large amount of electromagnetic and kinetic energy (much of the latter being quickly converted to thermal energy). Fission of a kilogram of plutonium-239 can produce an explosion equivalent to {{convert|21,000|tonTNT|lk=on}}. It is this energy that makes plutonium-239 useful in [[nuclear weapon]]s and [[nuclear reactor|reactors]].<ref name = "Heiserman1992" /> |

|||

The presence of the isotope [[plutonium-240]] in a sample limits its nuclear bomb potential, as plutonium-240 has a relatively high [[spontaneous fission]] rate (~440 fissions per second per gram—over 1,000 neutrons per second per gram),<ref>{{ |

The presence of the isotope [[plutonium-240]] in a sample limits its nuclear bomb potential, as plutonium-240 has a relatively high [[spontaneous fission]] rate (~440 fissions per second per gram—over 1,000 neutrons per second per gram),<ref>{{Cite web |last1=Glasstone |first1=Samuel |last2=Redman |first2=Leslie M. |date=June 1972 |title=An Introduction to Nuclear Weapons |url=http://www.doeal.gov/opa/docs/RR00171.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090827082245/http://www.doeal.gov/opa/docs/RR00171.pdf |archive-date=August 27, 2009 |publisher=Atomic Energy Commission Division of Military Applications |page=12 |id=WASH-1038}}</ref> raising the background neutron levels and thus increasing the risk of [[fizzle (nuclear test)|predetonation]].<ref>{{harvnb|Gosling|1999|p=40}}</ref> Plutonium is identified as either [[weapons-grade]], fuel-grade, or reactor-grade based on the percentage of plutonium-240 that it contains. Weapons-grade plutonium contains less than 7% plutonium-240. [[reactor-grade plutonium|Fuel-grade plutonium]] contains from 7% to less than 19%, and power reactor-grade contains 19% or more plutonium-240. [[plutonium-239#Supergrade plutonium|Supergrade plutonium]], with less than 4% of plutonium-240, is used in [[United States Navy|U.S. Navy]] weapons stored in proximity to ship and submarine crews, due to its lower radioactivity.<ref>{{Cite web |date=1996 |title=Plutonium: The First 50 Years |url=http://www.doeal.gov/SWEIS/DOEDocuments/004%20DOE-DP-0137%20Plutonium%2050%20Years.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130218162928/http://www.doeal.gov/SWEIS/DOEDocuments/004%20DOE-DP-0137%20Plutonium%2050%20Years.pdf |archive-date=February 18, 2013 |publisher=U.S. Department of Energy |id=DOE/DP-1037}}</ref> The isotope [[plutonium-238]] is not [[fissile#Fissile vs fissionable|fissile but can undergo nuclear fission]] easily with [[fast neutrons]] as well as alpha decay.<ref name="Heiserman1992" /> All plutonium isotopes can be "bred" into fissile material with one or more [[neutron absorption]]s, whether followed by [[beta decay]] or not. This makes non-fissile isotopes of plutonium a [[fertile material]]. |

||

{{cite web |

|||

|title = Plutonium: The First 50 Years |

|||

|publisher = U.S. Department of Energy |

|||

|date = 1996 |

|||

|id = DOE/DP-1037 |

|||

|url = http://www.doeal.gov/SWEIS/DOEDocuments/004%20DOE-DP-0137%20Plutonium%2050%20Years.pdf |

|||

|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130218162928/http://www.doeal.gov/SWEIS/DOEDocuments/004%20DOE-DP-0137%20Plutonium%2050%20Years.pdf |

|||

|archive-date=February 18, 2013 |

|||

}}</ref> The isotope [[plutonium-238]] is not [[fissile#Fissile vs fissionable|fissile but can undergo nuclear fission]] easily with [[fast neutrons]] as well as alpha decay.<ref name = "Heiserman1992" /> All plutonium isotopes can be "bred" into fissile material with one or more [[neutron absorption]]s, whether followed by [[beta decay]] or not. This makes non-fissile isotopes of Plutonium a [[fertile material]]. |

|||

===Isotopes and nucleosynthesis=== |

===Isotopes and nucleosynthesis=== |

||

[[File:PuIsotopes.svg|thumb|upright=1.5|Uranium-plutonium and thorium-uranium chains|alt=A diagram illustrating the interconversions between various isotopes of uranium, thorium, protactinium and plutonium]] |

[[File:PuIsotopes.svg|thumb|upright=1.5|Uranium-plutonium and thorium-uranium chains|alt=A diagram illustrating the interconversions between various isotopes of uranium, thorium, protactinium and plutonium]] |

||

{{Main|Isotopes of plutonium}} |

{{Main|Isotopes of plutonium}} |

||

Twenty [[radioisotope|radioactive isotopes]] of plutonium have been characterized. The longest-lived are plutonium-244, with a half-life of 80.8 million years, plutonium-242, with a half-life of 373,300 years, and plutonium-239, with a half-life of 24,110 years. All of the remaining radioactive isotopes have half-lives that are less than 7,000 years. This element also has eight [[meta state|metastable states]], though all have half-lives less than one second.<ref name |

Twenty [[radioisotope|radioactive isotopes]] of plutonium have been characterized. The longest-lived are plutonium-244, with a half-life of 80.8 million years, plutonium-242, with a half-life of 373,300 years, and plutonium-239, with a half-life of 24,110 years. All of the remaining radioactive isotopes have half-lives that are less than 7,000 years. This element also has eight [[meta state|metastable states]], though all have half-lives less than one second.<ref name="NNDC">{{Cite web |last=Sonzogni |first=Alejandro A. |date=2008 |title=Chart of Nuclides |url=http://www.nndc.bnl.gov/chart/ |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110721051025/http://www.nndc.bnl.gov/chart/ |archive-date=July 21, 2011 |access-date=September 13, 2008 |publisher=National Nuclear Data Center, [[Brookhaven National Laboratory]] |location=Upton}}</ref> Plutonium-244 has been found in interstellar space<ref name="WallnerFaestermann2015">{{Cite journal |last1=Wallner |first1=A. |last2=Faestermann |first2=T. |last3=Feige |first3=J. |last4=Feldstein |first4=C. |last5=Knie |first5=K. |last6=Korschinek |first6=G. |last7=Kutschera |first7=W. |last8=Ofan |first8=A. |last9=Paul |first9=M. |last10=Quinto |first10=F. |last11=Rugel |first11=G. |last12=Steier |first12=P. |year=2015 |title=Abundance of live 244Pu in deep-sea reservoirs on Earth points to rarity of actinide nucleosynthesis |journal=Nature Communications |volume=6 |pages=5956 |arxiv=1509.08054 |bibcode=2015NatCo...6.5956W |doi=10.1038/ncomms6956 |issn=2041-1723 |pmc=4309418 |pmid=25601158}}</ref> and it has the longest half-life of any non-primordial radioisotope. |

||

|url = http://www.nndc.bnl.gov/chart/ |

|||

|first = Alejandro A. |

|||

|last = Sonzogni |

|||

|title = Chart of Nuclides |

|||

|publisher = National Nuclear Data Center, [[Brookhaven National Laboratory]] |

|||

|access-date = September 13, 2008 |

|||

|date = 2008 |

|||

|location = Upton |

|||

|archive-date = July 21, 2011 |

|||

|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20110721051025/http://www.nndc.bnl.gov/chart/ |

|||

|url-status = dead |

|||

}}</ref> Plutonium-244 has been found in interstellar space<ref name="WallnerFaestermann2015">{{cite journal|last1=Wallner|first1=A.|last2=Faestermann|first2=T.|last3=Feige|first3=J.|last4=Feldstein|first4=C.|last5=Knie|first5=K.|last6=Korschinek|first6=G.|last7=Kutschera|first7=W.|last8=Ofan|first8=A.|last9=Paul|first9=M.|last10=Quinto|first10=F.|last11=Rugel|first11=G.|last12=Steier|first12=P.|title=Abundance of live 244Pu in deep-sea reservoirs on Earth points to rarity of actinide nucleosynthesis|journal=Nature Communications|volume=6|year=2015|pages=5956|issn=2041-1723|doi=10.1038/ncomms6956|pmid=25601158|pmc=4309418|arxiv=1509.08054|bibcode=2015NatCo...6.5956W}}</ref> and is has the longest half-life of any non-primordial radioisotope. |

|||

The known isotopes of plutonium range in [[mass number]] from 228 to 247. The primary decay modes of isotopes with mass numbers lower than the most stable isotope, plutonium-244, are spontaneous fission and [[alpha emission]], mostly forming uranium (92 [[proton]]s) and [[neptunium]] (93 protons) isotopes as [[decay product]]s (neglecting the wide range of daughter nuclei created by fission processes). The primary decay mode for isotopes with mass numbers higher than plutonium-244 is [[beta emission]], mostly forming [[americium]] (95 protons) isotopes as decay products. Plutonium-241 is the [[parent isotope]] of the [[neptunium decay series]], decaying to americium-241 via beta emission.<ref name |

The known isotopes of plutonium range in [[mass number]] from 228 to 247. The primary decay modes of isotopes with mass numbers lower than the most stable isotope, plutonium-244, are spontaneous fission and [[alpha emission]], mostly forming uranium (92 [[proton]]s) and [[neptunium]] (93 protons) isotopes as [[decay product]]s (neglecting the wide range of daughter nuclei created by fission processes). The primary decay mode for isotopes with mass numbers higher than plutonium-244 is [[beta emission]], mostly forming [[americium]] (95 protons) isotopes as decay products. Plutonium-241 is the [[parent isotope]] of the [[neptunium decay series]], decaying to americium-241 via beta emission.<ref name="NNDC" /><ref name="p340">{{harvnb|Heiserman|1992|p=340}}</ref> |

||

Plutonium-238 and 239 are the most widely synthesized isotopes.<ref name |

Plutonium-238 and 239 are the most widely synthesized isotopes.<ref name="Heiserman1992" /> Plutonium-239 is synthesized via the following reaction using uranium (U) and neutrons (n) via beta decay (β<sup>−</sup>) with neptunium (Np) as an intermediate:<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Kennedy |first1=J. W. |last2=Seaborg, G. T. |last3=Segrè, E. |last4=Wahl, A. C. |date=1946 |title=Properties of Element 94 |journal=Physical Review |volume=70 |issue=7–8 |pages=555–556 |bibcode=1946PhRv...70..555K |doi=10.1103/PhysRev.70.555 |doi-access=free}}</ref> |

||

:<chem> |

:<chem> |

||

| Line 159: | Line 58: | ||

</chem> |

</chem> |

||

Neutrons from the fission of uranium-235 are [[neutron capture|captured]] by uranium-238 nuclei to form uranium-239; a [[beta decay]] converts a neutron into a proton to form neptunium-239 (half-life 2.36 days) and another beta decay forms plutonium-239.<ref name |

Neutrons from the fission of uranium-235 are [[neutron capture|captured]] by uranium-238 nuclei to form uranium-239; a [[beta decay]] converts a neutron into a proton to form neptunium-239 (half-life 2.36 days) and another beta decay forms plutonium-239.<ref name="Greenwood1997p1259">{{harvnb|Greenwood|1997|p = 1259}}</ref> [[Egon Bretscher]] working on the British [[Tube Alloys]] project predicted this reaction theoretically in 1940.{{sfn|Clark|1961|pp=124–125}} |

||

Plutonium-238 is synthesized by bombarding uranium-238 with [[deuteron]]s (D, the nuclei of heavy [[hydrogen]]) in the following reaction:<ref>{{ |

Plutonium-238 is synthesized by bombarding uranium-238 with [[deuteron]]s (D, the nuclei of heavy [[hydrogen]]) in the following reaction:<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Seaborg |first1=Glenn T. |last2=McMillan, E. |last3=Kennedy, J. W. |last4=Wahl, A. C. |date=1946 |title=Radioactive Element 94 from Deuterons on Uranium |journal=Physical Review |volume=69 |issue=7–8 |pages=366 |bibcode=1946PhRv...69..366S |doi=10.1103/PhysRev.69.366}}</ref> |

||

:<math chem>\begin{align} |

:<math chem>\begin{align} |

||

| Line 168: | Line 67: | ||

\end{align}</math> |

\end{align}</math> |

||

In this process, a deuteron hitting uranium-238 produces two neutrons and neptunium-238, which spontaneously decays by emitting negative beta particles to form plutonium-238.{{sfn|Bernstein|2007|pp=76–77}} Plutonium-238 can also be produced by [[neutron irradiation]] of [[neptunium-237]].<ref>{{ |

In this process, a deuteron hitting uranium-238 produces two neutrons and neptunium-238, which spontaneously decays by emitting negative beta particles to form plutonium-238.{{sfn|Bernstein|2007|pp=76–77}} Plutonium-238 can also be produced by [[neutron irradiation]] of [[neptunium-237]].<ref>{{Cite web |last=Miotla |first=Dennis |date=21 April 2008 |title=Assessment of Plutonium-238 Production of Alternatives: Briefing for Nuclear Energy Advisory Committee |url=https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/NEGTN0NEAC_PU-238_042108.pdf |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220316130014/https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/NEGTN0NEAC_PU-238_042108.pdf |archive-date=March 16, 2022 |access-date=28 February 2022 |publisher=Energy.gov}}</ref> |

||

===Decay heat and fission properties=== |

===Decay heat and fission properties=== |

||

| Line 174: | Line 73: | ||

{| class="wikitable" |

{| class="wikitable" |

||

|+ Decay heat of plutonium isotopes<ref>{{ |

|+ Decay heat of plutonium isotopes<ref>{{Cite web |date=May 2001 |title=Can Reactor Grade Plutonium Produce Nuclear Fission Weapons? |url=http://www.cnfc.or.jp/e/proposal/reports/index.html |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210224141047/http://www.cnfc.or.jp/e/proposal/reports/index.html |archive-date=February 24, 2021 |access-date=January 30, 2010 |publisher=Council for Nuclear Fuel Cycle Institute for Energy Economics, Japan}}</ref> |

||

! Isotope !! [[Decay mode]] !! [[Half-life]] (years) !! [[Decay heat]] (W/kg) !! [[Spontaneous fission]] neutrons (1/(g·s)) !! Comment |

! Isotope !! [[Decay mode]] !! [[Half-life]] (years) !! [[Decay heat]] (W/kg) !! [[Spontaneous fission]] neutrons (1/(g·s)) !! Comment |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| Line 196: | Line 95: | ||

| 6.8 |

| 6.8 |

||

| 910 |

| 910 |

||

| The principal impurity in samples of the <sup>239</sup>Pu isotope. The plutonium grade is usually listed as percentage of <sup>240</sup>Pu. High spontaneous fission hinders use in nuclear weapons. |

| The principal impurity in samples of the <sup>239</sup>Pu isotope. The plutonium grade is usually listed as percentage of <sup>240</sup>Pu. High rate of spontaneous fission hinders use in nuclear weapons. |

||

|- |

|- |

||

! [[plutonium-241|<sup>241</sup>Pu]] |

! [[plutonium-241|<sup>241</sup>Pu]] |

||

| Line 214: | Line 113: | ||

===Compounds and chemistry=== |

===Compounds and chemistry=== |

||

{{Main|Plutonium compounds}} |

|||

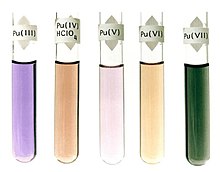

[[File:Plutonium in solution.jpg|thumb|Various oxidation states of plutonium in solution|alt=Five fluids in glass test tubes: violet, Pu(III); dark brown, Pu(IV)HClO4; light purple, Pu(V); light brown, Pu(VI); dark green, Pu(VII)]] |

[[File:Plutonium in solution.jpg|thumb|Various oxidation states of plutonium in solution|alt=Five fluids in glass test tubes: violet, Pu(III); dark brown, Pu(IV)HClO4; light purple, Pu(V); light brown, Pu(VI); dark green, Pu(VII)]] |

||

At room temperature, pure plutonium is silvery in color but gains a tarnish when oxidized.<ref>{{harvnb|Heiserman|1992|p=339}}</ref> The element displays four common ionic [[oxidation state]]s in [[aqueous solution]] and one rare one:<ref name |

At room temperature, pure plutonium is silvery in color but gains a tarnish when oxidized.<ref>{{harvnb|Heiserman|1992|p=339}}</ref> The element displays four common ionic [[oxidation state]]s in [[aqueous solution]] and one rare one:<ref name="CRC2006p4-27" /> |

||

* Pu(III), as Pu<sup>3+</sup> (blue lavender) |

* Pu(III), as Pu<sup>3+</sup> (blue lavender) |

||

* Pu(IV), as Pu<sup>4+</sup> (yellow brown) |

* Pu(IV), as Pu<sup>4+</sup> (yellow brown) |

||

* Pu(V), as {{chem|PuO|2|+}} (light pink){{efn|group = note|The {{chem|PuO|2|+}} ion is unstable in solution and will disproportionate into Pu<sup>4+</sup> and {{chem|PuO|2|2+}}; the Pu<sup>4+</sup> will then oxidize the remaining {{chem|PuO|2|+}} to {{chem|PuO|2|2+}}, being reduced in turn to Pu<sup>3+</sup>. Thus, aqueous solutions of {{chem|PuO|2|+}} tend over time towards a mixture of Pu<sup>3+</sup> and {{chem|PuO|2|2+}}. [[Uranium#Aqueous chemistry|{{chem|UO|2|+}}]] is unstable for the same reason.<ref>{{ |

* Pu(V), as {{chem|PuO|2|+}} (light pink){{efn|group = note|The {{chem|PuO|2|+}} ion is unstable in solution and will disproportionate into Pu<sup>4+</sup> and {{chem|PuO|2|2+}}; the Pu<sup>4+</sup> will then oxidize the remaining {{chem|PuO|2|+}} to {{chem|PuO|2|2+}}, being reduced in turn to Pu<sup>3+</sup>. Thus, aqueous solutions of {{chem|PuO|2|+}} tend over time towards a mixture of Pu<sup>3+</sup> and {{chem|PuO|2|2+}}. [[Uranium#Aqueous chemistry|{{chem|UO|2|+}}]] is unstable for the same reason.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Crooks |first=William J. |date=2002 |title=Nuclear Criticality Safety Engineering Training Module 10 – Criticality Safety in Material Processing Operations, Part 1 |url=http://ncsp.llnl.gov/ncset/Module10.pdf |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060320153404/http://ncsp.llnl.gov/ncset/Module10.pdf |archive-date=March 20, 2006 |access-date=February 15, 2006}}</ref>}} |

||

|title = Nuclear Criticality Safety Engineering Training Module 10 – Criticality Safety in Material Processing Operations, Part 1 |

|||

|url = http://ncsp.llnl.gov/ncset/Module10.pdf |

|||

|access-date = February 15, 2006 |

|||

|date = 2002 |

|||

|last = Crooks |

|||

|first = William J. |

|||

|url-status = dead |

|||

|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20060320153404/http://ncsp.llnl.gov/ncset/Module10.pdf |

|||

|archive-date = March 20, 2006 |

|||

}}</ref>}} |

|||

* Pu(VI), as {{chem|PuO|2|2+}} (pink orange) |

* Pu(VI), as {{chem|PuO|2|2+}} (pink orange) |

||

* Pu(VII), as {{chem|PuO|5|3-}} (green)—the heptavalent ion is rare. |

* Pu(VII), as {{chem|PuO|5|3-}} (green)—the heptavalent ion is rare. |

||

The color shown by plutonium solutions depends on both the oxidation state and the nature of the acid [[anion]].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Matlack |first=George |title=A Plutonium Primer: An Introduction to Plutonium Chemistry and its Radioactivity |date=2002 |publisher=Los Alamos National Laboratory |id=LA-UR-02-6594}}</ref> It is the acid anion that influences the degree of [[complex (chemistry)|complexing]]—how atoms connect to a central atom—of the plutonium species. Additionally, the formal +2 oxidation state of plutonium is known in the complex [K(2.2.2-cryptand)] [Pu<sup>II</sup>Cp″<sub>3</sub>], Cp″ = C<sub>5</sub>H<sub>3</sub>(SiMe<sub>3</sub>)<sub>2</sub>.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Windorff |first1=Cory J. |last2=Chen |first2=Guo P |last3=Cross |first3=Justin N |last4=Evans |first4=William J. |last5=Furche |first5=Filipp |last6=Gaunt |first6=Andrew J. |last7=Janicke |first7=Michael T. |last8=Kozimor |first8=Stosh A. |last9=Scott |first9=Brian L. |year=2017 |title=Identification of the Formal +2 Oxidation State of Plutonium: Synthesis and Characterization of <nowiki>{</nowiki>Pu<sup>II</sup><nowiki>[</nowiki>C<sub>5</sub>H<sub>3</sub>(SiMe<sub>3</sub>)<sub>2</sub><nowiki>]</nowiki><sub>3</sub><nowiki>}</nowiki><sup>−</sup> |journal=J. Am. Chem. Soc. |volume=139 |issue=11 |pages=3970–3973 |doi=10.1021/jacs.7b00706 |pmid=28235179}}</ref> |

|||

The color shown by plutonium solutions depends on both the oxidation state and the nature of the acid [[anion]].<ref>{{cite book |

|||

|last = Matlack |

|||

|first = George |

|||

|title = A Plutonium Primer: An Introduction to Plutonium Chemistry and its Radioactivity |

|||

|publisher = Los Alamos National Laboratory |

|||

|date = 2002 |

|||

|id = LA-UR-02-6594 |

|||

}}</ref> It is the acid anion that influences the degree of [[complex (chemistry)|complexing]]—how atoms connect to a central atom—of the plutonium species. Additionally, the formal +2 oxidation state of plutonium is known in the complex [K(2.2.2-cryptand)] [Pu<sup>II</sup>Cp″<sub>3</sub>], Cp″ = C<sub>5</sub>H<sub>3</sub>(SiMe<sub>3</sub>)<sub>2</sub>.<ref>{{cite journal|doi=10.1021/jacs.7b00706|pmid=28235179|title=Identification of the Formal +2 Oxidation State of Plutonium: Synthesis and Characterization of <nowiki>{</nowiki>Pu<sup>II</sup><nowiki>[</nowiki>C<sub>5</sub>H<sub>3</sub>(SiMe<sub>3</sub>)<sub>2</sub><nowiki>]</nowiki><sub>3</sub><nowiki>}</nowiki><sup>−</sup>|year=2017|first1=Cory J.|last1=Windorff|first2=Guo P|last2=Chen|first3=Justin N|last3=Cross|first4=William J.|last4=Evans|first5=Filipp|last5= Furche|first6=Andrew J.|last6=Gaunt|first7=Michael T.|last7=Janicke|first8=Stosh A.|last8=Kozimor|first9=Brian L.|last9=Scott|journal=J. Am. Chem. Soc.|volume=139|issue=11|pages=3970–3973}}</ref> |

|||

A +8 oxidation state is possible as well in the volatile tetroxide {{chem|Pu|O|4}}.<ref name |

A +8 oxidation state is possible as well in the volatile tetroxide {{chem|Pu|O|4}}.<ref name="zaitsevskii">{{Cite journal |last1=Zaitsevskii |first1=Andréi |last2=Mosyagin |first2=Nikolai S. |last3=Titov |first3=Anatoly V. |last4=Kiselev |first4=Yuri M. |date=21 July 2013 |title=Relativistic density functional theory modeling of plutonium and americium higher oxide molecules |journal=The Journal of Chemical Physics |volume=139 |issue=3 |pages=034307 |bibcode=2013JChPh.139c4307Z |doi=10.1063/1.4813284 |pmid=23883027}}</ref> Though it readily decomposes via a reduction mechanism similar to {{chem|Fe|O|4}}, {{chem|Pu|O|4}} can be stabilized in alkaline solutions and [[chloroform]].<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Kiselev |first1=Yu. M. |last2=Nikonov |first2=M. V. |last3=Dolzhenko |first3=V. D. |last4=Ermilov |first4=A. Yu. |last5=Tananaev |first5=I. G. |last6=Myasoedov |first6=B. F. |date=17 January 2014 |title=On existence and properties of plutonium(VIII) derivatives |journal=Radiochimica Acta |volume=102 |issue=3 |pages=227–237 |doi=10.1515/ract-2014-2146 |s2cid=100915090}}</ref><ref name="zaitsevskii" /> |

||

Metallic plutonium is produced by reacting [[plutonium tetrafluoride]] with [[barium]], [[calcium]] or [[lithium]] at 1200 °C.<ref>{{harvnb|Eagleson|1994|p=840}}</ref> Metallic plutonium is attacked by [[acid]]s, [[oxygen]], and steam but not by [[alkalis]] and dissolves easily in concentrated [[hydrochloric acid|hydrochloric]], [[hydroiodic acid|hydroiodic]] and [[perchloric acid]]s.<ref name="Miner1968p545">{{harvnb|Miner|1968|p = 545}}</ref> Molten metal must be kept in a [[vacuum]] or an [[inert atmosphere]] to avoid reaction with air.<ref name="Miner1968p542">{{harvnb|Miner|1968|p = 542}}</ref> At 135 °C the metal will ignite in air and will explode if placed in [[carbon tetrachloride]].<ref name="Emsley2001" /> |

|||

Metallic plutonium is produced by reacting [[plutonium tetrafluoride]] with [[barium]], [[calcium]] or [[lithium]] at 1200 °C.<ref> |

|||

{{harvnb|Eagleson|1994|p=840}}</ref> Metallic plutonium is attacked by [[acid]]s, [[oxygen]], and steam but not by [[alkalis]] and dissolves easily in concentrated [[hydrochloric acid|hydrochloric]], [[hydroiodic acid|hydroiodic]] and [[perchloric acid]]s.<ref name = "Miner1968p545">{{harvnb|Miner|1968|p = 545}}</ref> Molten metal must be kept in a [[vacuum]] or an [[inert atmosphere]] to avoid reaction with air.<ref name = "Miner1968p542">{{harvnb|Miner|1968|p = 542}}</ref> At 135 °C the metal will ignite in air and will explode if placed in [[carbon tetrachloride]].<ref name = "Emsley2001" /> |

|||

[[File:Plutonium pyrophoricity.jpg|thumb|Plutonium [[pyrophoricity]] can cause it to look like a glowing ember under certain conditions.|alt=Black block of Pu with red spots on top and yellow powder around it]] |

[[File:Plutonium pyrophoricity.jpg|thumb|Plutonium [[pyrophoricity]] can cause it to look like a glowing ember under certain conditions.|alt=Black block of Pu with red spots on top and yellow powder around it]] |

||

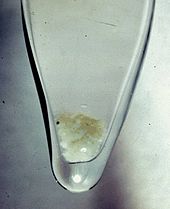

[[File:96602765.lowres.jpeg|thumb|upright|alt=Glass vial of brownish-white snow-like precipitation of plutonium hydroxide|Twenty micrograms of pure plutonium hydroxide]] |

[[File:96602765.lowres.jpeg|thumb|upright|alt=Glass vial of brownish-white snow-like precipitation of plutonium hydroxide|Twenty micrograms of pure plutonium hydroxide]] |

||

Plutonium is a reactive metal. In moist air or moist [[argon]], the metal oxidizes rapidly, producing a mixture of [[oxide]]s and [[hydride]]s.<ref name |

Plutonium is a reactive metal. In moist air or moist [[argon]], the metal oxidizes rapidly, producing a mixture of [[oxide]]s and [[hydride]]s.<ref name="WISER" /> If the metal is exposed long enough to a limited amount of water vapor, a powdery surface coating of PuO<sub>2</sub> is formed.<ref name="WISER" /> Also formed is [[plutonium hydride]] but an excess of water vapor forms only PuO<sub>2</sub>.<ref name="Miner1968p545" /> |

||

Plutonium shows enormous, and reversible, reaction rates with pure hydrogen, forming [[plutonium hydride]].<ref name |

Plutonium shows enormous, and reversible, reaction rates with pure hydrogen, forming [[plutonium hydride]].<ref name="HeckerPlutonium" /> It also reacts readily with oxygen, forming PuO and PuO<sub>2</sub> as well as intermediate oxides; plutonium oxide fills 40% more volume than plutonium metal. The metal reacts with the [[halogen]]s, giving rise to [[chemical compound|compounds]] with the general formula PuX<sub>3</sub> where X can be [[plutonium(III) fluoride|F]], [[plutonium(III) chloride|Cl]], [[plutonium(III) bromide|Br]] or I and PuF<sub>4</sub> is also seen. The following oxyhalides are observed: PuOCl, PuOBr and PuOI. It will react with carbon to form PuC, nitrogen to form PuN and [[silicon]] to form PuSi<sub>2</sub>.<ref name="CRC2006p4-27" /><ref name="Emsley2001" /> |

||

The [[Organometallic chemistry|organometallic]] chemistry of plutonium complexes is typical for [[Organoactinide chemistry|organoactinide]] species; a characteristic example of an organoplutonium compound is [[plutonocene]].<ref name="Greenwood1997p1259" /><ref name=" |

The [[Organometallic chemistry|organometallic]] chemistry of plutonium complexes is typical for [[Organoactinide chemistry|organoactinide]] species; a characteristic example of an organoplutonium compound is [[plutonocene]].<ref name="Greenwood1997p1259" /><ref name="Apostolidis-2017">{{Cite journal |last1=Apostolidis |first1=Christos |last2=Walter |first2=Olaf |last3=Vogt |first3=Jochen |last4=Liebing |first4=Phil |last5=Maron |first5=Laurent |last6=Edelmann |first6=Frank T. |date=2017 |title=A Structurally Characterized Organometallic Plutonium(IV) Complex |journal=Angewandte Chemie International Edition |language=en |volume=56 |issue=18 |pages=5066–5070 |doi=10.1002/anie.201701858 |issn=1521-3773 |pmc=5485009 |pmid=28371148}}</ref> Computational chemistry methods indicate an enhanced [[Covalent bond|covalent]] character in the plutonium-ligand bonding.<ref name="HeckerPlutonium" /><ref name="Apostolidis-2017" /> |

||

Powders of plutonium, its hydrides and certain oxides like Pu<sub>2</sub>O<sub>3</sub> |

Powders of plutonium, its hydrides and certain oxides like Pu<sub>2</sub>O<sub>3</sub> |

||

are [[pyrophoricity|pyrophoric]], meaning they can ignite spontaneously at ambient temperature and are therefore handled in an inert, dry atmosphere of nitrogen or argon. Bulk plutonium ignites only when heated above 400 °C. Pu<sub>2</sub>O<sub>3</sub> spontaneously heats up and transforms into PuO<sub>2</sub>, which is stable in dry air, but reacts with water vapor when heated.<ref name="NucSafety" /> |

are [[pyrophoricity|pyrophoric]], meaning they can ignite spontaneously at ambient temperature and are therefore handled in an inert, dry atmosphere of nitrogen or argon. Bulk plutonium ignites only when heated above 400 °C. Pu<sub>2</sub>O<sub>3</sub> spontaneously heats up and transforms into PuO<sub>2</sub>, which is stable in dry air, but reacts with water vapor when heated.<ref name="NucSafety" /> |

||

[[Crucible]]s used to contain plutonium need to be able to withstand its strongly [[redox|reducing]] properties. [[Refractory metals]] such as [[tantalum]] and [[tungsten]] along with the more stable oxides, [[boride]]s, [[carbide]]s, [[nitride]]s and [[silicide]]s can tolerate this. Melting in an [[electric arc furnace]] can be used to produce small ingots of the metal without the need for a crucible.<ref name |

[[Crucible]]s used to contain plutonium need to be able to withstand its strongly [[redox|reducing]] properties. [[Refractory metals]] such as [[tantalum]] and [[tungsten]] along with the more stable oxides, [[boride]]s, [[carbide]]s, [[nitride]]s and [[silicide]]s can tolerate this. Melting in an [[electric arc furnace]] can be used to produce small ingots of the metal without the need for a crucible.<ref name="Miner1968p542" /> |

||

[[Cerium]] is used as a chemical simulant of plutonium for development of containment, extraction, and other technologies.<ref>{{ |

[[Cerium]] is used as a chemical simulant of plutonium for development of containment, extraction, and other technologies.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Crooks, W. J. |display-authors=etal |date=2002 |title=Low Temperature Reaction of ReillexTM HPQ and Nitric Acid |url=http://sti.srs.gov/fulltext/ms2000068/ms2000068.html |url-status=live |journal=Solvent Extraction and Ion Exchange |volume=20 |issue=4–5 |pages=543–559 |doi=10.1081/SEI-120014371 |s2cid=95081082 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110614053034/http://sti.srs.gov/fulltext/ms2000068/ms2000068.html |archive-date=June 14, 2011 |access-date=January 24, 2010}}</ref> |

||

====Electronic structure==== |

====Electronic structure==== |

||

Plutonium is an element in which the [[f shell|5f electrons]] are the transition border between delocalized and localized; it is therefore considered one of the most complex elements.<ref name="physicsworld.com">{{ |

Plutonium is an element in which the [[f shell|5f electrons]] are the transition border between delocalized and localized; it is therefore considered one of the most complex elements.<ref name="physicsworld.com">{{Cite news |last=Dumé, Belle |date=November 20, 2002 |title=Plutonium is also a superconductor |publisher=PhysicsWeb.org |url=http://physicsworld.com/cws/article/news/16443 |url-status=live |access-date=January 24, 2010 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120112184014/http://physicsworld.com/cws/article/news/16443 |archive-date=January 12, 2012}}</ref> The anomalous behavior of plutonium is caused by its electronic structure. The energy difference between the 6d and 5f subshells is very low. The size of the 5f shell is just enough to allow the electrons to form bonds within the lattice, on the very boundary between localized and bonding behavior. The proximity of energy levels leads to multiple low-energy electron configurations with near equal energy levels. This leads to competing 5f<sup>n</sup>7s<sup>2</sup> and 5f<sup>n−1</sup>6d<sup>1</sup>7s<sup>2</sup> configurations, which causes the complexity of its chemical behavior. The highly directional nature of 5f orbitals is responsible for directional covalent bonds in molecules and complexes of plutonium.<ref name="HeckerPlutonium" /> |

||

===Alloys=== |

===Alloys=== |

||

Plutonium can form alloys and intermediate compounds with most other metals. Exceptions include lithium, [[sodium]], [[potassium]], [[rubidium]] and [[caesium]] of the [[alkali metal]]s; and [[magnesium]], calcium, [[strontium]], and barium of the [[alkaline earth metal]]s; and [[europium]] and [[ytterbium]] of the [[rare earth metal]]s.<ref name |

Plutonium can form alloys and intermediate compounds with most other metals. Exceptions include lithium, [[sodium]], [[potassium]], [[rubidium]] and [[caesium]] of the [[alkali metal]]s; and [[magnesium]], calcium, [[strontium]], and barium of the [[alkaline earth metal]]s; and [[europium]] and [[ytterbium]] of the [[rare earth metal]]s.<ref name="Miner1968p545" /> Partial exceptions include the refractory metals [[chromium]], [[molybdenum]], [[niobium]], tantalum, and tungsten, which are soluble in liquid plutonium, but insoluble or only slightly soluble in solid plutonium.<ref name="Miner1968p545" /> Gallium, aluminium, americium, [[scandium]] and cerium can stabilize the δ phase of plutonium for room temperature. [[Silicon]], [[indium]], [[zinc]] and [[zirconium]] allow formation of metastable δ state when rapidly cooled. High amounts of [[hafnium]], [[holmium]] and [[thallium]] also allows some retention of the δ phase at room temperature. Neptunium is the only element that can stabilize the α phase at higher temperatures.<ref name="HeckerPlutonium" /> |

||

Plutonium alloys can be produced by adding a metal to molten plutonium. If the alloying metal is sufficiently reductive, plutonium can be added in the form of oxides or halides. The δ phase plutonium–gallium and plutonium–aluminium alloys are produced by adding plutonium(III) fluoride to molten gallium or aluminium, which has the advantage of avoiding dealing directly with the highly reactive plutonium metal.<ref>{{harvnb|Moody| Hutcheon|Grant|2005|p=169}}</ref> |

Plutonium alloys can be produced by adding a metal to molten plutonium. If the alloying metal is sufficiently reductive, plutonium can be added in the form of oxides or halides. The δ phase plutonium–gallium and plutonium–aluminium alloys are produced by adding plutonium(III) fluoride to molten gallium or aluminium, which has the advantage of avoiding dealing directly with the highly reactive plutonium metal.<ref>{{harvnb|Moody| Hutcheon|Grant|2005|p=169}}</ref> |

||

* [[Plutonium-gallium alloy|Plutonium–gallium]] is used for stabilizing the δ phase of plutonium, avoiding the α-phase and α–δ related issues. Its main use is in [[pit (nuclear weapon)|pits]] of [[nuclear weapons design|implosion nuclear weapons]].<ref>{{ |

* [[Plutonium-gallium alloy|Plutonium–gallium]] is used for stabilizing the δ phase of plutonium, avoiding the α-phase and α–δ related issues. Its main use is in [[pit (nuclear weapon)|pits]] of [[nuclear weapons design|implosion nuclear weapons]].<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Kolman, D. G. |last2=Colletti, L. P. |name-list-style=amp |date=2009 |title=The aqueous corrosion behavior of plutonium metal and plutonium–gallium alloys exposed to aqueous nitrate and chloride solutions |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=0o4DnYptWdgC&pg=PA71 |url-status=live |journal=ECS Transactions |publisher=Electrochemical Society |volume=16 |issue=52 |page=71 |bibcode=2009ECSTr..16Z..71K |doi=10.1149/1.3229956 |isbn=978-1-56677-751-3 |s2cid=96567022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220316125950/https://books.google.com/books?id=0o4DnYptWdgC&pg=PA71 |archive-date=March 16, 2022 |access-date=December 2, 2020}}</ref> |

||

* '''Plutonium–aluminium''' is an alternative to the Pu–Ga alloy. It was the original element considered for δ phase stabilization, but its tendency to react with the alpha particles and release neutrons reduces its usability for nuclear weapon pits. Plutonium–aluminium alloy can be also used as a component of [[nuclear fuel]].<ref>{{harvnb|Hurst|Ward|1956}}</ref> |

* '''Plutonium–aluminium''' is an alternative to the Pu–Ga alloy. It was the original element considered for δ phase stabilization, but its tendency to react with the alpha particles and release neutrons reduces its usability for nuclear weapon pits. Plutonium–aluminium alloy can be also used as a component of [[nuclear fuel]].<ref>{{harvnb|Hurst|Ward|1956}}</ref> |

||

* '''Plutonium–gallium–cobalt''' alloy (PuCoGa<sub>5</sub>) is an [[unconventional superconductor]], showing superconductivity below 18.5 K, an order of magnitude higher than the highest between [[heavy fermion]] systems, and has large critical current.<ref name="physicsworld.com" /><ref>{{cite web<!--Citation bot -->|url=http://www.lanl.gov/orgs/mpa/files/mrhighlights/LALP-06-072.pdf|author=Curro, N. J.|title=Unconventional superconductivity in PuCoGa<sub>5</sub>|date=Spring 2006|publisher=Los Alamos National Laboratory|access-date=January 24, 2010|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110722062226/http://www.lanl.gov/orgs/mpa/files/mrhighlights/LALP-06-072.pdf|archive-date=July 22, 2011|url-status=dead}}</ref> |

* '''Plutonium–gallium–cobalt''' alloy (PuCoGa<sub>5</sub>) is an [[unconventional superconductor]], showing superconductivity below 18.5 K, an order of magnitude higher than the highest between [[heavy fermion]] systems, and has large critical current.<ref name="physicsworld.com" /><ref>{{cite web<!--Citation bot -->|url=http://www.lanl.gov/orgs/mpa/files/mrhighlights/LALP-06-072.pdf|author=Curro, N. J.|title=Unconventional superconductivity in PuCoGa<sub>5</sub>|date=Spring 2006|publisher=Los Alamos National Laboratory|access-date=January 24, 2010|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110722062226/http://www.lanl.gov/orgs/mpa/files/mrhighlights/LALP-06-072.pdf|archive-date=July 22, 2011|url-status=dead}}</ref> |

||

| Line 279: | Line 161: | ||

==Occurrence== |

==Occurrence== |

||

[[File:2019-11-22_Radioactive_Plutonium_sample_at_Questacon_museum,_Canberra,_Australia.jpg|thumb|Sample of plutonium metal displayed at the [[Questacon]] museum]] |

[[File:2019-11-22_Radioactive_Plutonium_sample_at_Questacon_museum,_Canberra,_Australia.jpg|thumb|Sample of plutonium metal displayed at the [[Questacon]] museum]] |

||

Trace amounts of plutonium-238, plutonium-239, plutonium-240, and plutonium-244 can be found in nature. Small traces of plutonium-239, a few [[parts per notation|parts per trillion]], and its decay products are naturally found in some concentrated ores of uranium,<ref name="Miner1968p541" /> such as the [[natural nuclear fission reactor]] in [[Oklo]], [[Gabon]].<ref>{{Cite web |date=2004 |title=Oklo: Natural Nuclear Reactors |url=http://www.ocrwm.doe.gov/factsheets/doeymp0010.shtml |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081020201724/http://www.ocrwm.doe.gov/factsheets/doeymp0010.shtml |archive-date=October 20, 2008 |access-date=November 16, 2008 |publisher=U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Civilian Radioactive Waste Management}}</ref> The ratio of plutonium-239 to uranium at the [[Cigar Lake Mine]] uranium deposit ranges from {{val|2.4|e=-12}} to {{val|44|e=-12}}.<ref name="Cigar">{{Cite journal |last1=Curtis |first1=David |last2=Fabryka-Martin |first2=June |last3=Paul |first3=Dixon |last4=Cramer |first4=Jan |date=1999 |title=Nature's uncommon elements: plutonium and technetium |url=https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc704244/ |url-status=live |journal=Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta |volume=63 |issue=2 |pages=275–285 |bibcode=1999GeCoA..63..275C |doi=10.1016/S0016-7037(98)00282-8 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210627232349/https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc704244/ |archive-date=June 27, 2021 |access-date=June 29, 2019}}</ref> These trace amounts of <sup>239</sup>Pu originate in the following fashion: on rare occasions, <sup>238</sup>U undergoes spontaneous fission, and in the process, the nucleus emits one or two free neutrons with some kinetic energy. When one of these neutrons strikes the nucleus of another <sup>238</sup>U atom, it is absorbed by the atom, which becomes <sup>239</sup>U. With a relatively short half-life, <sup>239</sup>U decays to <sup>239</sup>Np, which decays into <sup>239</sup>Pu.{{sfn|Bernstein|2007|pp=75–77}}<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Hoffman |first1=D. C. |last2=Lawrence |first2=F. O. |last3=Mewherter |first3=J. L. |last4=Rourke |first4=F. M. |date=1971 |title=Detection of Plutonium-244 in Nature |journal=Nature |volume=234 |issue=5325 |pages=132–134 |bibcode=1971Natur.234..132H |doi=10.1038/234132a0 |s2cid=4283169}}</ref> Finally, exceedingly small amounts of plutonium-238, attributed to the extremely rare [[double beta decay]] of uranium-238, have been found in natural uranium samples.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Peterson |first=Ivars |date=December 7, 1991 |title=Uranium displays rare type of radioactivity |journal=[[Science News]] |publisher=[[Wiley-Blackwell]] |volume=140 |issue=23 |page=373 |doi=10.2307/3976137 |jstor=3976137}}</ref> |

|||

Trace amounts of plutonium-238, plutonium-239, plutonium-240, and plutonium-244 can be found in nature. Small traces of plutonium-239, a few [[parts per notation|parts per trillion]], and its decay products are naturally found in some concentrated ores of uranium,<ref name = "Miner1968p541" /> such as the [[natural nuclear fission reactor]] in [[Oklo]], [[Gabon]].<ref> |

|||

{{cite web |

|||

|url = http://www.ocrwm.doe.gov/factsheets/doeymp0010.shtml |

|||

|title = Oklo: Natural Nuclear Reactors |

|||

|publisher = U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Civilian Radioactive Waste Management |

|||

|date = 2004 |

|||

|access-date = November 16, 2008 |

|||

|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20081020201724/http://www.ocrwm.doe.gov/factsheets/doeymp0010.shtml |

|||

|archive-date = October 20, 2008 |

|||

}}</ref> The ratio of plutonium-239 to uranium at the [[Cigar Lake Mine]] uranium deposit ranges from {{val|2.4|e=-12}} to {{val|44|e=-12}}.<ref name = "Cigar">{{cite journal |

|||

|journal = Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta |

|||

|volume = 63 |

|||

|issue = 2 |

|||

|pages = 275–285 |

|||

|date = 1999 |

|||

|doi = 10.1016/S0016-7037(98)00282-8 |

|||

|title = Nature's uncommon elements: plutonium and technetium |

|||

|first1 = David |

|||

|last1 = Curtis |

|||

|last2 = Fabryka-Martin |

|||

|first2 = June |

|||

|last3 = Paul |

|||

|first3 = Dixon |

|||

|last4 = Cramer |

|||

|first4 = Jan |

|||

|bibcode = 1999GeCoA..63..275C |

|||

|url = https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc704244/ |

|||

|access-date = June 29, 2019 |

|||

|archive-date = June 27, 2021 |

|||

|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20210627232349/https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc704244/ |

|||

|url-status = live |

|||

}}</ref> These trace amounts of <sup>239</sup>Pu originate in the following fashion: on rare occasions, <sup>238</sup>U undergoes spontaneous fission, and in the process, the nucleus emits one or two free neutrons with some kinetic energy. When one of these neutrons strikes the nucleus of another <sup>238</sup>U atom, it is absorbed by the atom, which becomes <sup>239</sup>U. With a relatively short half-life, <sup>239</sup>U decays to <sup>239</sup>Np, which decays into <sup>239</sup>Pu.{{sfn|Bernstein|2007|pp=75–77}}<ref>{{cite journal|doi = 10.1038/234132a0|title= Detection of Plutonium-244 in Nature|journal = Nature|pages = 132–134|date = 1971|last1 = Hoffman|first1 = D. C.|last2 = Lawrence|first2 = F. O.|last3 = Mewherter|first3 = J. L.|last4 = Rourke|first4 = F. M.|volume = 234|bibcode = 1971Natur.234..132H|issue=5325|s2cid= 4283169}}</ref> Finally, exceedingly small amounts of plutonium-238, attributed to the extremely rare [[double beta decay]] of uranium-238, have been found in natural uranium samples.<ref>{{cite journal|last = Peterson|title = Uranium displays rare type of radioactivity|date = December 7, 1991|first = Ivars|doi = 10.2307/3976137|jstor = 3976137|publisher = [[Wiley-Blackwell]]|volume = 140|issue = 23|page = 373|journal = [[Science News]]}}</ref> |

|||

Due to its relatively long half-life of about 80 million years, it was suggested that [[plutonium-244]] occurs naturally as a [[primordial nuclide]], but early reports of its detection could not be confirmed.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Hoffman |first1=D. C. |last2=Lawrence |first2=F. O. |last3=Mewherter |first3=J. L. |last4=Rourke |first4=F. M. |date=1971 |title=Detection of Plutonium-244 in Nature |journal=Nature |volume=234 |issue=5325 |pages=132–134 |bibcode=1971Natur.234..132H |doi=10.1038/234132a0 |s2cid=4283169 |id=Nr. 34}}</ref> Based on its likely initial abundance in the Solar System, present experiments as of 2022 are likely about an order of magnitude away from detecting live primordial <sup>244</sup>Pu.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Wu |first1=Yang |last2=Dai |first2=Xiongxin |first3=Shan |last3=Xing |first4=Maoyi |last4=Luo |first5=Marcus |last5=Christl |first6=Hans-Arno |last6=Synal |first7=Shaochun |last7=Hou |date=2022 |title=Direct search for primordial <sup>244</sup>Pu in Bayan Obo bastnaesite |url=http://www.ccspublishing.org.cn/article/doi/10.1016/j.cclet.2022.03.036?pageType=en |journal=Chinese Chemical Letters |volume=33 |issue=7 |pages=3522–3526 |doi=10.1016/j.cclet.2022.03.036 |access-date=29 January 2024}}</ref> However, its long half-life ensured its circulation across the solar system before its [[extinct radionuclide|extinction]],<ref name="Turner-2004">{{Cite journal |last1=Turner |first1=Grenville |last2=Harrison |first2=T. Mark |last3=Holland |first3=Greg |last4=Mojzsis |first4=Stephen J. |last5=Gilmour |first5=Jamie |date=2004-01-01 |title=Extinct <sup>244</sup>Pu in Ancient Zircons |url=https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/3cda/5d558ee8b37160d83d66d7ce0fdb47b3ef75.pdf |url-status=dead |journal=Science |volume=306 |issue=5693 |pages=89–91 |bibcode=2004Sci...306...89T |doi=10.1126/science.1101014 |jstor=3839259 |pmid=15459384 |s2cid=11625563 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200211020817/https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/3cda/5d558ee8b37160d83d66d7ce0fdb47b3ef75.pdf |archive-date=2020-02-11}}</ref> and indeed, evidence of the spontaneous fission of extinct <sup>244</sup>Pu has been found in meteorites.<ref name="Hutcheon-1972">{{Cite journal |last1=Hutcheon |first1=I. D. |last2=Price |first2=P. B. |date=1972-01-01 |title=Plutonium-244 Fission Tracks: Evidence in a Lunar Rock 3.95 Billion Years Old |journal=Science |volume=176 |issue=4037 |pages=909–911 |bibcode=1972Sci...176..909H |doi=10.1126/science.176.4037.909 |jstor=1733798 |pmid=17829301 |s2cid=25831210}}</ref> The former presence of <sup>244</sup>Pu in the early Solar System has been confirmed, since it manifests itself today as an excess of its daughters, either <sup>232</sup>[[thorium|Th]] (from the alpha decay pathway) or [[xenon]] isotopes (from its [[spontaneous fission]]). The latter are generally more useful, because the chemistries of thorium and plutonium are rather similar (both are predominantly tetravalent) and hence an excess of thorium would not be strong evidence that some of it was formed as a plutonium daughter.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Kunz |first1=Joachim |last2=Staudacher |first2=Thomas |last3=Allègre |first3=Claude J. |date=1998-01-01 |title=Plutonium-Fission Xenon Found in Earth's Mantle |journal=Science |volume=280 |issue=5365 |pages=877–880 |bibcode=1998Sci...280..877K |doi=10.1126/science.280.5365.877 |jstor=2896480 |pmid=9572726}}</ref> <sup>244</sup>Pu has the longest half-life of all transuranic nuclides and is produced only in the [[r-process]] in [[supernova]]e and colliding [[neutron star]]s; when nuclei are ejected from these events at high speed to reach Earth, <sup>244</sup>Pu alone among transuranic nuclides has a long enough half-life to survive the journey, and hence tiny traces of live interstellar <sup>244</sup>Pu have been found in the deep sea floor. Because <sup>240</sup>Pu also occurs in the [[decay chain]] of <sup>244</sup>Pu, it must thus also be present in [[secular equilibrium]], albeit in even tinier quantities.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Wallner |first1=A. |last2=Faestermann |first2=T. |last3=Feige |first3=J. |last4=Feldstein |first4=C. |last5=Knie |first5=K. |last6=Korschinek |first6=G. |last7=Kutschera |first7=W. |last8=Ofan |first8=A. |last9=Paul |first9=M. |last10=Quinto |first10=F. |last11=Rugel |first11=G. |last12=Steiner |first12=P. |date=30 March 2014 |title=Abundance of live <sup>244</sup>Pu in deep-sea reservoirs on Earth points to rarity of actinide nucleosynthesis |journal=Nature Communications |volume=6 |page=5956 |arxiv=1509.08054 |bibcode=2015NatCo...6.5956W |doi=10.1038/ncomms6956 |pmc=4309418 |pmid=25601158 |s2cid=119286045}}</ref> |

|||

Due to its relatively long half-life of about 80 million years, it was suggested that [[plutonium-244]] occurs naturally as a [[primordial nuclide]], but early reports of its detection could not be confirmed.<ref> |

|||

{{cite journal |

|||

|first1 = D. C. |

|||

|last1 = Hoffman |

|||

|last2 = Lawrence|first2=F. O.|last3=Mewherter|first3=J. L.|last4=Rourke|first4=F. M. |

|||

|title = Detection of Plutonium-244 in Nature |

|||

|journal = Nature |

|||

|id = Nr. 34 |

|||

|date = 1971 |

|||

|pages = 132–134 |

|||

|doi = 10.1038/234132a0 |

|||

|volume = 234 |

|||

|bibcode = 1971Natur.234..132H |

|||

|issue=5325|s2cid = 4283169 |

|||